Roots & Branches is an award-winning, weekly newspaper column begun in 1998 that currently is published in the Altoona Mirror. It’s the only syndicated column on genealogy in Pennsylvania!

Posted July 6, 2025 by James Beidler | 4 Comments

Some years ago I first was contacted by “another” Jim Beidler, this one who lives in Ohio, and eventually we became Facebook Friends.

As a matter of fact, one time I ham-fistedly “tagged” him in a picture of myself while on vacation at Bryce Canyon in Utah.

We’ve talked electronically now and again over the years, but last month I finally had the chance to meet Jim and his wife Lori, along with my girlfriend Katy Bodenhorn, who’s also a genealogist.

The “other” Jim is a retired college IT guy and he and his wife travel a bit, especially to visit their children in Colorado.

At one time in the past, Jim and I had electronically chit-chatted and I wasn’t able to help him with his Beidler line, but from the memory book Jim’s late father Richard had compiled, it appears they were from the Jacob Beidler line, the early Mennonite immigrant who settled in Bucks County.

I recall that the late, great Don Yoder (initiator of so many things in Pennsylvania German genealogy) telling me that he knew where the Beidler (or in the original German spelling, Beutler) family’s hometown was … but that fact is either buried deep in my files or no longer existent!

But back to the “other” Jim Beidler. We had a wonderful meal together north of Columbus … kindred spirits even if whatever blood we share is tiny and distant at best.

Jim and Lori took care of dinner, and Katy and I vowed to return the favor to give them incentive to visit Pennsylvania!

***

Remember that concept “things found on the way to something else?”

Well, last week I was helping lay plans for a Pennsylvania German genealogy series for the Historic Trappe organization when its executive director Lisa Minardi sprang a surprise on me.

First she reminded me about the Chester County History Center’s mammoth mapping project for present-day Chester and Delaware counties, which shows landowners a year into the American Revolution and can be found at the URL, https://storymaps.arcgis.com/stories/9cef8b93eaa94faf8e106edbb737ef1c

“And be sure to mention Jim Duffin’s project that started as a mapping of landowners in West Philadelphia circa 1777 and is now being expanded to all of what was then Philadelphia County”—meaning today’s Montgomery County in addition to the city of Philadelphia.

Say that again? This pricked up my interest since my immigrant Johannes Beydeler settled in the vicinity of Trappe in today’s Montgomery County, but I had never been able to tease into shape the four tracts of land he bought.

Well, all it took was Duffin’s map that had enough parcels identified on their map for me to finally put those four tracts together! The URL for Duffin’s map in progress is https://maps.archives.upenn.edu/WestPhila1777/about.php

As I expected, there is nothing left from the period of Beidler occupancy (the homestead land just missed becoming a Target), and alas Johannes’s widow Anna Maria sold the land in 1775, soon after Johannes’s death, so no Beidler will appear on this map. But it’s a good thing knowing exactly where their land was!

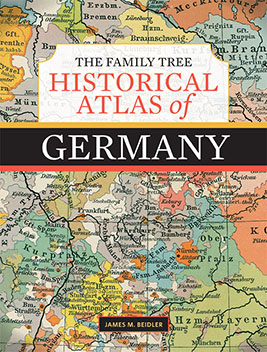

Have You Bought Your Copy?

The Family Tree Historical Atlas of Germany, by James M. Beidler

This new atlas brought to you by author James M. Beidler gives you all the maps you need to research your German-speaking ancestors. The areas that area now Germany—as well as Austria, Switzerland and other territories in which German-speaking people resided—are examined from Roman times to the present day, including detail maps from the prime emigration period during the Second Reich. More than a hundred full-color maps!